This article was originally published at The National Observer.

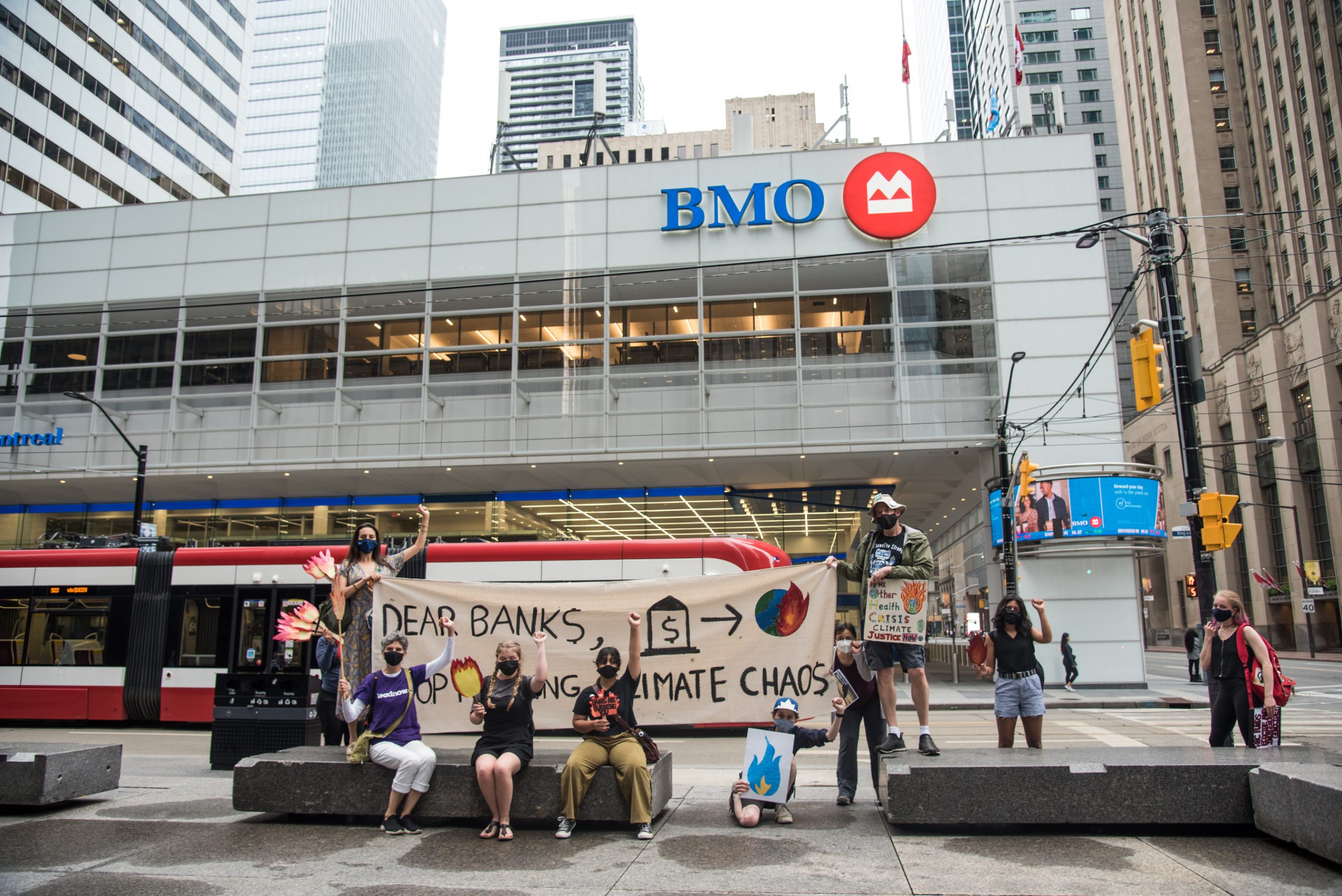

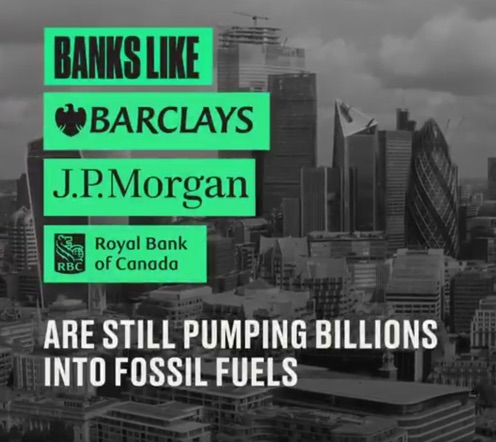

Canada’s five largest banks have a problem. And it’s a big one. Big to the tune of $726 billion, according to the new Banking on Climate Chaos report published March 24. RBC, TD, Scotiabank, CIBC and BMO have poured that much money into fossil fuel companies since the Paris Agreement was signed Dec. 12, 2015. RBC is at the top of the list in Canada and is the world’s fifth-largest financier of fossil fuels — and it’s not just oil and gas. Despite it being the 21st century, RBC keeps financing the fuel of the 19th century, putting more than $14 billion into coal mining and coal-related companies from 2018 to 2020.

It’s a shameful record for our banking industry. One that needs to change.

It’s clear that we are not accelerating fast enough to the just, green and equitable future that we all need. Global emissions continue to climb despite a blip from pandemic-related shutdowns. Indigenous rights-violating and air-polluting projects are continuing to get built. One of the things that is slowing us down is every dollar that continues to go into fossil fuel companies and expansion projects. Those holding our savings and mortgages and controlling the flow of money into coal, oil and gas — RBC and the rest of Canadian banking gang — need to wake up and smell the CO2.

While we should be moving at full speed with investments in real climate solutions — like renewables, retrofitting businesses, climate resiliency projects and carbon-neutral housing — we are being slowed down by continuing to build out new oil and gas infrastructure, such as TMX, Line 5, and LNG in B.C. Between 2016 and 2020, RBC financed $79 billion of business with companies actively expanding fossil fuel production, not just operating existing facilities and pipelines.

Let’s think of it this way: If you need to drive 100km/h in your electric car to get to your destination on time, you wouldn’t hitch a tar-sands excavator to the back. That’s what the $726 billion that Canada’s big banks are pouring into fossil fuel companies is — a motherlode slowing down our collective progress.

RBC and the others want to eat their cake and have it, too. They tout increasing investments in intentionally air-quoted “sustainable industries.” In February, RBC announced half a trillion dollars would go into sustainable investments by 2025. First rule of balanced nutrition, though: You can’t eat an apple to make up for gorging on doughnuts. Putting $100 billion a year into sustainable investments for the next half decade doesn’t make up for continuing to put tens of billions into tar sands, coal, pipelines and other oil and gas projects and companies. And it certainly doesn’t get your bank’s financed emissions down to net zero.

One of the other emerging problems with these big sustainable investment commitments the banks are making is that there is very little transparency on what connotes one of these investments. Recently, it was disclosed that Enbridge — builder of the Line 3 tar sands pipeline that’s making regular headlines in Minnesota for violating Indigenous rights — received a $1-billion sustainability-linked loan from some Canadian banks. If the most egregious, rights-violating fossil fuel-expanding projects can be categorized as “sustainable finance,” then we’re into Orwellian “Peace Is War” territory.

Last point on sustainable investments is that it’s easy to make bold-sounding promises to invest more in the sector of the economy that is booming. Renewables-based portfolios have consistently and significantly outperformed traditional energy stocks for the past 10 years. Any bank executive who doesn’t want to do more business in one of the economy’s most profitable sectors should probably be fired. Based on the financing record of the banks revealed on March 24, explicit decisions from the C-suite have been made to continue to offer lines of credit and underwrite fossil fuel companies to the tune of billions.

Which brings us back to the why of this story. Why are RBC and the other Canadian banks choosing to continue to do business with the companies that are at the forefront of driving the climate crisis we are facing today and in the years to come? The simple answer is that the banks are still making money in the short term off this line of business. Mergers, acquisitions, short-term revolving credit facilities make money for banks regardless of the industry.

Most of them are not going to be on the hook when, in 10 years time, that 2021-built pipeline or gas plant starts operating at half capacity or is prematurely shut down. And they won’t be on the line when a shale company goes bankrupt. But that calculus is beginning to change in certain subsectors, particularly for our Canadian banks. As more and more international banks, insurers and other institutions like pension funds restrict investments in the tar sands or coal, Canadian banks, known as the banks of miners and energy companies, are increasingly overexposed to these extreme energy subsectors. That’s a risk shareholders, who convene next month for all of our banks, should be concerned about.

It’s clear the calculus has to change. As the science says, we have less than a decade to change the direction of the ship we are on, and the last thing we need is to be spending money on new fossil fuel projects that have a 40-year lifespan, locking us into continued fossil fuel use. It is past the time for the value of our climate and the rights of Indigenous peoples to be worked into the decision-making equation over business deals, even if that means rapidly scaling down ties with an industry Canadian banks have been doing business with and enabling for decades. Fossil fuel companies are failing across the board to realize tangible and immediate-term transition plans that match the climate science.

When RBC proclaims the transition can’t be too disruptive or that it needs to be there to help the likes of Enbridge, it’s simply an excuse to continue to bank on climate destruction.

We’ve got no more time for excuses. What we do have time for is banks like RBC recognizing their big problem and taking real action to address it. This means dropping the false green rhetoric along with the financing of expansion projects including coal and tar sands is the start. Let’s see if the banks will rise to the challenge on their own, or if their customers and shareholders will have to force it.

Richard Brooks is the climate finance director with Stand.earth.

This article was originally published on the National Observer website.