Where to bank for the climate? RBC ranks dead last

When most people first learn that their financial institutions are contributing in major ways to making the climate crisis worse, one of the first questions they typically ask is, so where should I bank then?

While the issue is complicated, Matt Price of Investors for Paris Compliance recently wrote this helpful steer.

Canada’s banks are particularly carbon entangled, with our big five each featuring in the top 20 largest funders of fossil fuels in the world. While we need to keep lobbying governments to better regulate both the fossil fuel sector and the financial sector, climate-concerned Canadians can also take action by letting their bank know they are unhappy with its performance and either threatening to shift their business elsewhere or actually doing it.

But shift where? We get this question a lot because we carefully parse the climate disclosures of Canada’s banks to compare them with best practices given by science. They are each now talking a good game about getting to “net zero” by 2050, but the reality is unfortunately less than advertised. In this piece, we hope to provide a general ranking of where the banks are in their policy journey so that you can make your own decisions on how or whether to engage with them.

The best financial institutions tend to be credit unions, of which Canada has plenty of good ones that offer most banking services. You can find one near you using this tool. Regional bank Laurentian ranks second. After that, each choice is filled with challenges as the better banks have made some tangible commitments on fossil fuels, but continue to pour hundreds of millions into their expansion every year.

Dead last in the rankings? RBC:

As Spiderman fans know, with great power comes great responsibility. RBC is Canada’s largest bank and, as such, sets the tone. Unfortunately, RBC is Canada’s largest funder of fossil fuels, fifth largest in the world. Moreover, the tone we are hearing from RBC is decidedly pro-fossil fuels.

Incredibly, RBC is doing less than even the banks in the prior category. Unlike the other banks, it is yet to set any targets for its financed emissions and underestimates its current emissions by failing to account for what’s called “Scope 3” or downstream emissions.

Recently, RBC put out a report that called for increasing oil and gas production in Canada. Note that the International Energy Agency found getting to net zero means no investment in new fossil fuels — we already have enough to cook the planet. Only dodgy math could argue the opposite.

For these reasons, RBC is bringing up the rear.

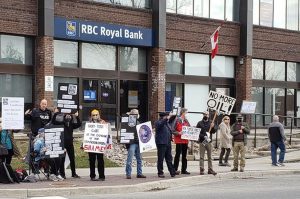

Which is why RBC staff and customers are going to continue to see images like these, wherever they go. And hopefully more customers walking out their door.